Analysis: A closer look at a Scottish law that could criminalise parents and Christians

The Scottish Government published its controversial proposals for a ‘conversion practices’ law on 9 January. The proposals are ill-thought-through and pose a serious risk to the ordinary work of churches and to loving parenting. They raise the alarming prospect of ordinary parents and Christians facing up to seven years in prison for daring to disagree with radical LGBT ideology.

We’ve written several blogs about this already, but we wanted to share with you a more in-depth analysis:

What is left to outlaw?

Activists say a new law is needed to prevent abuse against the LGBT community. But there are already strong laws on the statute book to protect gay and trans people. Thankfully, existing legislation tackles verbal and physical abuse against adults and children in Scotland today.

The Scottish Government’s consultation says its proposals are designed to criminalise “conversion practices that would not be considered to be threatening or abusive” [page. 25].

Legal advice from eminent human rights lawyer Aidan O’Neill KC is clear that existing law already tackles abusive and coercive practices. Instead, what the Scottish Government calls “‘gaps in the law" is really “behaviour that does not… constitute ‘degrading treatment’, does not constitute the infliction of physical abuse or mental or emotional abuse… and does not constitute harassment because of sexual orientation or gender reassignment” [para. 3.5].

We can deduce two things from this: 1) a new law in this area is unnecessary; and 2) the proposals pose a serious risk to legitimate behaviour, since the threshold is far lower than genuinely harmful behaviour.

“legally incoherent” definition

The necessity for a clear definition – and the difficulty in attaining one – has been accepted both by those concerned about a new law, and by those proposing one.

The Scottish Government has been at pains to stress the efforts it has made to ensure the wording of its proposals is suitable. But its proposed definition of ‘conversion practices’ is in fact, so ill-defined that any practice which is considered not to ‘affirm’ a person’s sexual orientation or gender identity could be caught.

Roddy Dunlop KC, the Dean of the Faculty of Advocates, has said the definition is not “legally coherent”. The Law Society of Scotland, which represents over 13,000 solicitors, has similarly expressed concern that the definition is “too broad” and “may criminalise legitimate behaviour”.

Too broad to be the basis for a new criminal law

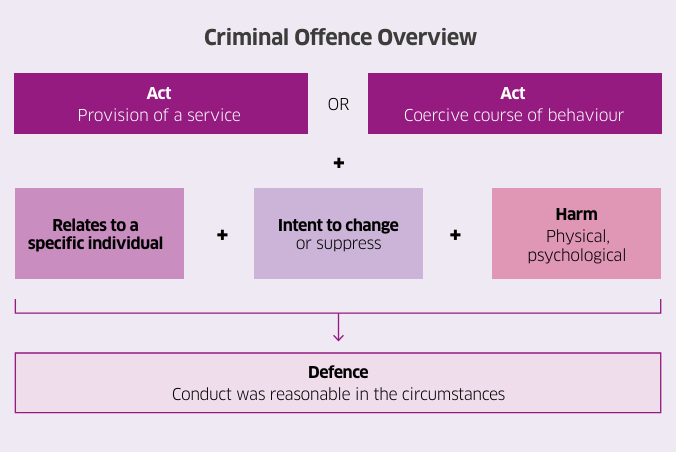

The Scottish Government insists that we are to view its proposals as a ‘package of measures’, claiming that because there are multiple ‘tests’ that must be met, this raises the threshold of the offence. But when you consider each aspect of the proposed new criminal offence (see diagram below), it becomes clear just how easy it is for an innocent person to trip each of the ‘tests’

1. The consultation says a “coercive course of behaviour” includes “controlling of the victim’s day-to-day activities” and “pressuring the victim to act in a particular way” [§ 104]. But this could easily be a description of normal, everyday parenting. It is crucial that parents, as part of their ongoing responsibility, exercise appropriate control of their child’s day-to-day activities. As recognised across human rights frameworks, parents must be free to bring up their children in accordance with their beliefs. The example given in the consultation confirms the fear that ordinary parenting is at risk: “preventing someone from dressing in a way that reflects their sexual orientation or gender identity” [§ 105]. Aidan O’Neill KC states:

"This definition of coercion would clearly therefore include parents seeking to control how their child ‘presents’ in terms of, say clothes, make-up, and hairstyle or imposing restrictions on where their child might go and whom they might see. Thus parents who actively and consistently and directly oppose ‘their child’s decision to, for example, present as a different gender from that given at birth’ (see § 108) would be committing a criminal offence” [para. 3.28].

A mum who stops her twelve-year-old son from going to school in a dress and make-up – on more than one occasion – would therefore meet the threshold of the offence and could face prosecution.

As for religious practice, the consultation says “provision of advice and guidance by a religious leader” would only be captured where there is coercion [§ 103]. But it simultaneously explains that coercion includes “emphatic directives accompanied by forceful… statements intended to pressure the individual”. Few Christians would understand their activity in these terms, but urging someone to repent because they are endangering their soul, for example, could be deemed to meet this threshold.

2. The consultation makes it clear that the word ‘suppression’ is included for the express purpose of “widen[ing] the scope of legislation” [§ 56]. But despite being a key term in the proposed definition, “suppression” is not clearly defined in the consultation.

Suppressing a person’s sexual orientation or gender identity is said to include “controlling a person’s appearance (e.g. clothes, make-up, hairstyle)” and “restricting where a person goes and who they see” [§ 50]. But these are just clinical ways of describing innocent and necessary features of parenting. Parents regularly limit what their child can wear, where they can go and who they can see. Such a catch-all definition of ‘suppression’ even means that a parent seeking to prevent their child viewing pornography could be accused of a conversion practice, since they are ‘suppressing’ the child’s expression of their ‘sexual orientation’.

The Scottish Government claims its intention is not to criminalise “the exercise of parental responsibilities and rights” [§ 41]. But it is clear the proposals would put loving parents at risk of prosecution for merely trying to guide their children to the path they believe is best for them.

The consultation also says promoting celibacy is an act of suppression. This is a direct limitation of freedom of religious belief, since celibacy is the mainstream, historic Christian teaching for the unmarried, regardless of a person’s sexual desires. All biblical teaching in line with these beliefs could therefore meet the ‘suppression’ test. No one should be afraid that encouraging or supporting someone to live in accordance with the Bible’s teaching will lead to prosecution.

3. The Scottish Government claims that the requirement that “harm” is evidenced is a key safeguard. However, harm includes ‘psychological harm’, which is defined to include the extremely low and subjective threshold of “distress”. This subjectivity is increased by the absence of any requirement to prove that harm had been intended or foreseen by the accused. The victim need only feel harmed [§ 83]. This sets the bar far too low, given how easy it is to claim distress and how difficult it is to disprove. It would capture a person acting with good intentions, merely on the basis of another’s hurt feelings.

This is of particular concern to anyone who holds a position that strongly contrasts with LGBT thinking, as no matter how good the intentions of their conduct, someone who disapproves of their viewpoint can accuse them of causing distress. The proposed ‘harm’ test is a serious threat to those holding out the Christian sexual ethic, or parents with gender-critical views.

4.At first glance, the proposed “defence of reasonableness” sounds appealing, but it is far too narrow to protect innocent behaviour. The consultation document repeatedly emphasises the limits of the defence. It says it could be used in “a very small number of circumstances” [§ 122], and even suggests that it is “difficult to envisage circumstances” in which it would apply [§ 123].

Aidan O’Neill KC describes it as “vague and unspecified” [para. 3.25], adding that “the legislation provides no definition or test or example of what may be considered to be ‘reasonable’ such as to constitute a defence against a prosecution for behaviour otherwise apparently criminalised” [para. 3.52].

As further demonstration of the highly limited nature of this test, the consultation says the defence could “potentially apply in situations where the specific day-to-day controls implemented by a parent were to prevent a child from engaging in illegal or dangerous behaviour” [§ 124]. Not only does this imply that ordinary parenting is in scope as described above, but Aidan O’Neill KC points out that this “example makes no sense in terms of how the proposed legislation is currently drafted”. He explains:

“The doctrine of double effect posits that if the primary intention of a parent in implementing any specific day-to-day controls were to prevent their child engaging in illegal or dangerous behaviour, then it might be said to be a foreseeable (though not necessarily intended) effect that the child might subjectively experience these restriction as what the legislation would term ‘coercive suppression’ of the child’s sexual orientation or gender identity. But that, on the legislation’s own terms, would not be sufficient to establish the requisite mens rea for the parent to be found guilty of the offence of engaging in ‘conversion practices’. In such circumstances the reasonableness defence would simply not apply” [para. 3.53].

Uncertainty over how far the law extends would inevitably lead to a chilling effect on legitimate behaviour. Individuals will not want to engage in discussion about matters of sex and sexuality out of fear it will result in prosecution. As the Free Church of Scotland has pointed out, “the only way for someone to be absolutely sure they were not committing an offence would be to adopt an affirming attitude”.

Analysis: A closer look at a Scottish law that could criminalise parents and Christians

2024-04-26 10:36:08Cass Report highlights major risks posed by conversion therapy law

2024-04-12 14:57:11